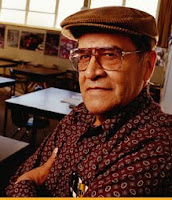

Like many others, I was saddened to learn this morning of Jaime Escalante’s passing. I vividly remember being inspired by his story, both as it was portrayed by Edward James Olmos in Stand and Deliver, and as it unfolded after the film was released.

Mr. Escalante found himself at the center of a controversy that still surrounds California schools today. What’s the problem? Low student performance. Huge achievement gap between minority students (who are the majority in most of our urban schools). Overwhelmingly powerful unions. Overburdened teachers. Apathetic teachers. Parents who are completely disconnected from the education system because they are either focused on survival or dealing with their own personal issues. Inadequate school funding.

Sound familiar? It should.

Mr. Escalante dealt with it in a way that I deeply admired, and that had a profound effect on my own career in education. He lit a candle. He ignored the naysayers, and the union, and all the negative forces around him, and he did everything he could to make a difference in the lives of the youth he taught. He not only had high expectations for them (a buzzword that has become so overused that most people don’t even know what it would really look like in the classroom anymore), but he demanded excellence from his students – and then he put his money (a.k.a. his time) where his mouth was, and he provided the support they needed to meet his demands. To paraphrase Gandhi, he decided that he would be the change he wanted in the world, and it almost killed him.

When the movie first came out, I had mixed feelings about it. On the one hand, who could not be inspired by his selfless and inspirational teaching and the results he got? On the other hand, I was a bit offended by the implication that teachers should have to give up their personal lives, huge amounts of time with their families, and even their health in order to be successful at their jobs.

As time went on, I began to understand that something is terribly wrong with a system that would demand such incredible sacrifice on the part of a teacher, yet I know teachers who give as much as Mr. Escalante every day, even to this very day. Make no mistake about it, he was, and is, not alone in his dedication, his ability to inspire children, and his belief that he can make a difference by lighting his candle and making change in his classroom, with his students. In spite of this, all of the characters you remember from the movie telling him to work less and laughing at him for believing that those kids could really achieve are still around even though the faces and names have changed. They are all over the state, in every school and district, and the system has ground to a halt largely because of them.

They play a game of blame, insisting that everyone else is responsible for the failing state of our schools- especially the children and their families. They show up at exactly their contracted time 30 minutes before the bell in the morning and they leave at exactly the time their contract says their day is over. I have seen them stand up in the middle of student presentations at after school sessions and walk out because the clock chimed “contract” and it was their time to go. They keep such a close eye on their own rights, time, and compensation that they have completely lost sight of the children who depend on them. Yes, I know they would angrily object to my characterization, but I have seen them for years in my work in the schools, I have met them, I know them. They can’t hide from me.

I am hoping the day is coming when they can’t hide from the rest of California anymore, either.

The unions are so powerful in California that people are afraid to speak out because the second they do the unions cast them as a teacher-hater. Politicians who attempt real reform are quickly beaten back. Social security may be the third rail of politics nationally, but there is no doubt that meaningful school reform and standing up to the unions to accomplish it form the third rail of California politics.

Mr. Escalante taught his students about the importance of las ganas. You have to really want it. To accomplish anything difficult, you have to really, really want it. You have to work hard at it. You have to sacrifice for it. That’s what our schools need. Advocates who are willing to work hard to make a change because they really, really want it. And not just a few, but thousands of advocates.

Some will do that work in their classrooms, but we need others who will do it as school leaders in the front offices of schools, as district leaders in the district offices, as trustees in the board rooms across the state, and as parents everywhere, in all of those settings.

The time has long passed when we should have started recognizing effective teachers with higher pay and job security, and that we deal with ineffective teachers (and administrators) by helping them on their way to a new profession.

I don’t know when the tipping point was reached – that point when unions, and apathy, and self-interest took control of our schools out of the hands of effective teachers, administrators, parents, and local communities – but I know that it’s time to take it back.

Mr. Escalante showed us what it looks like when a teacher has las ganas to make a difference. We know it’s possible. I wonder what our system would look like if thousands of us across the spectrum let that desire loose, too.

It is my hope that Mr. Escalante’s legacy will be that others, who may have been inspired by his life but not inspired enough to change and act, will reflect on his contribution to education and decide to pick up the torch and keep the movement he started moving forward. If one man can make such a difference, imagine what all of us could do.

Rest in peace, Mr. Escalante. We will miss you….and thank you.